Report on the Survey of 2016 Nephrology Fellows

Location Tops the List of Important Factors in Evaluating Job Offers

Leah Masselink, PhD

Milken Institute School of Public Health

Edward Salsberg, MPA

Leo Quigley, MPH

Nicholas Mehfoud, MS

George Washington University School of Nursing

Ashté Collins, MD

George Washington University School of Medicine

Preface

Physicians in training represent the future practitioners in their field and provide a picture of the future supply. The experience of those completing their training and about to embark on their careers is also an indicator of physician demand in their specialty. For these reasons, the George Washington University Health Workforce Institute (GWU HWI) research team and the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) have conducted an annual online survey of current nephrology fellows and trainees beginning in 2014 to obtain data on demographic and educational background, educational debt, career plans, job search experiences, and factors influencing job opportunities and choices.

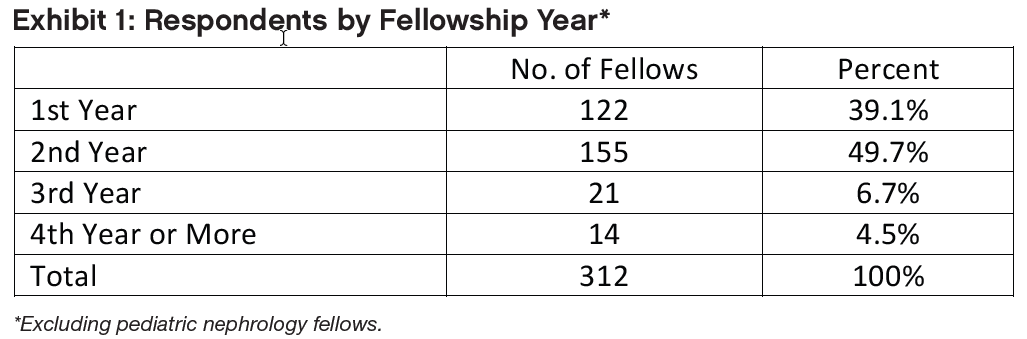

In 2016, the survey tool—adapted from the University at Albany Center for Health Workforce Studies (CHWS) annual NY State Resident Exit Survey and slightly modified from 2014 and 2015—was distributed to 1223 ASN Fellow/Trainee members (to whom ASN offers free membership) in June and July 2016. Three hundred and fifteen (315) fellows or trainees provided informed consent and responded to the survey questions for an overall response rate of 25.8%. Among the 863 fellows in their first and second year of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)–accredited training programs, we received responses from 277 fellows (32.1% response rate). The response rate for second year fellows was 36.1% (155 of 429). (The basic nephrology fellowship is 2 years, but many stay on for an additional year or two for subspecialty training or research.) This report presents demographic information for respondents in all years of fellowship and training, as well as job market experiences and fellows’ plans for those completing their second year of fellowship or beyond. It also presents data on job offers accepted by nephrology fellows and their assessments of the overall state of the specialty and job market. For all of the statistical tests presented, we considered probability values <0.05 to be statistically significant.

Key Findings

Respondents to the 2016 Nephrology Fellow Survey had a similar demographic profile to 2014 and 2015 respondents: 60% or more were international medical graduates (IMGs) and about 60% were male. The largest age group was 31–35 years, with IMGs significantly older than US medical graduates (USMGs) (35.0 years vs. 32.5 years, respectively—p<0.01). The majority of IMGs (68.7%) had no educational debt, while half (50.0%) of USMGs had at least $100,000 of debt.

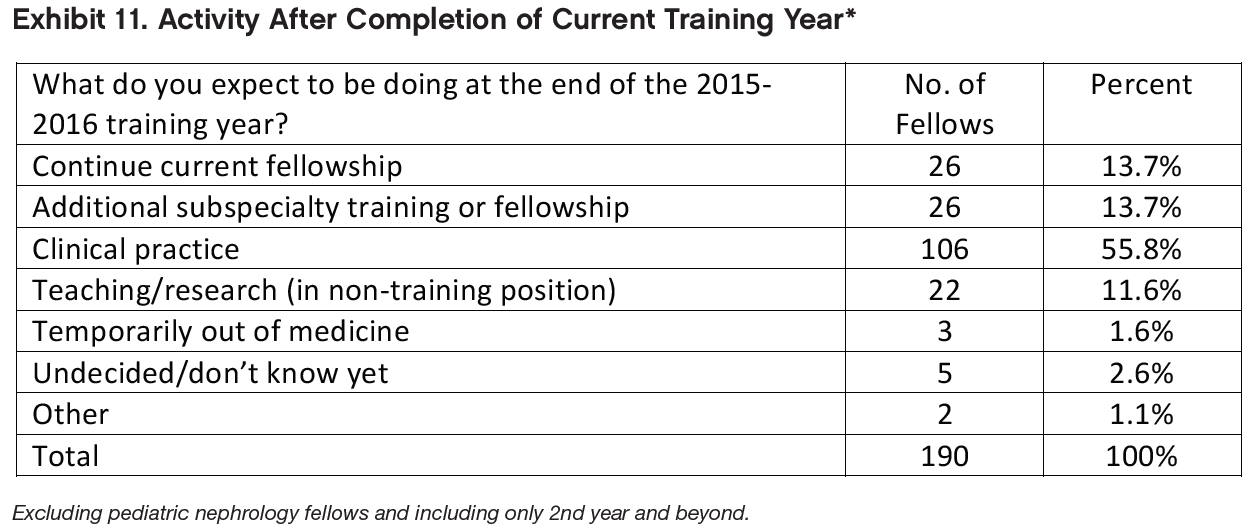

Among respondents in their second year of fellowship or beyond who indicated their plans for the upcoming year, the largest proportion indicated that they planned to enter clinical nephrology practice (55.8%). The next largest groups (13.7% each) intended to continue in their current fellowships or pursue additional subspecialty training. Frequently reported areas of continuing training included research and transplant nephrology.

Job market experiences continue to be starkly different for IMG and USMG fellows: IMGs were more likely than USMG fellows to report applying for large numbers of jobs, having difficulty finding a satisfactory position, and changing plans because of limited opportunities.

Not surprisingly, the most important factor considered in looking for a practice position was the location. The second- and third-most cited factor (as “very important” or “important”) were frequency of weekend duties and frequency of overnight call. Weekend and overnight work may reflect the nature of much of nephrology practice today and may be of concern to both nephrology fellows and residents who do not select the specialty.

Among nephrology fellows who had searched for jobs, perceptions of local nephrology job opportunities were improved since 2015: while 24.6% reported that there were many or some nephrology practice opportunities within 50 miles of their training sites in 2015, the proportion reporting the same in 2016 increased to 37.7%.

There was a statistically significant difference in IMG and USMG fellows’ assessments of local nephrology practice opportunities (p<0.05), but no difference between their assessments of national practice opportunities (p=0.25).

Among respondents who had accepted job offers and indicated their anticipated practice setting, the largest group (42.9%) reported that they planned to work in nephrology group practices. Another 20.4% reported that they planned to work in academic nephrology practices, and 10.2% each said they planned to work with multispecialty group practices and academic multispecialty practices. Other settings included 2-person partnerships (7.1%) and hospitals (6.1%).

Fellows’ anticipated salaries in 2016 were similar to 2014 and 2015; the median anticipated salary for all demographic groups (by IMG status and sex) was between $175,000 and $199,999. Anticipated incentive income was relatively small for all demographic groups ($5000 or less).

Fellows reported receiving a variety of incentives for accepting their primary jobs. Frequently cited incentives included income guarantees, support for maintenance of certification (MOC) and continuing medical education (CME), and career development opportunities.

A small number of fellows who had accepted employment reported having secondary jobs in addition to their primary positions. Frequently cited secondary jobs included medical directorships with dialysis providers, hospital care, moonlighting, and joint ventures with dialysis providers.

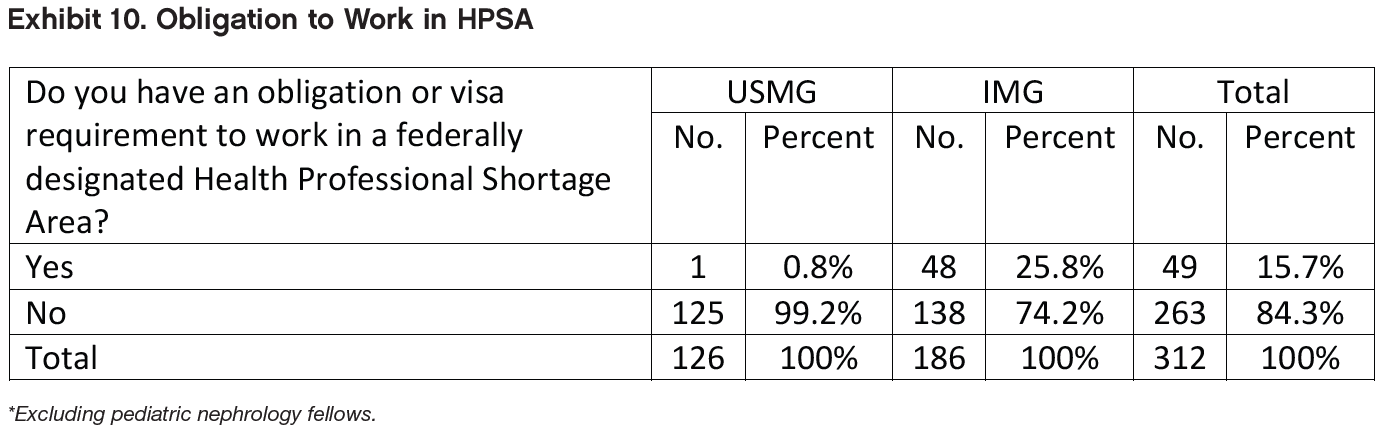

As in 2014 and 2015, IMGs appear to be making an important contribution to care in underserved areas. While 48 IMGs (25.8%) indicated an obligation to work in a federally designated Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA), only 1 (0.8%) USMG did so. The difference in the distribution of HPSA service obligations by IMG status was highly significant (p<0.01).

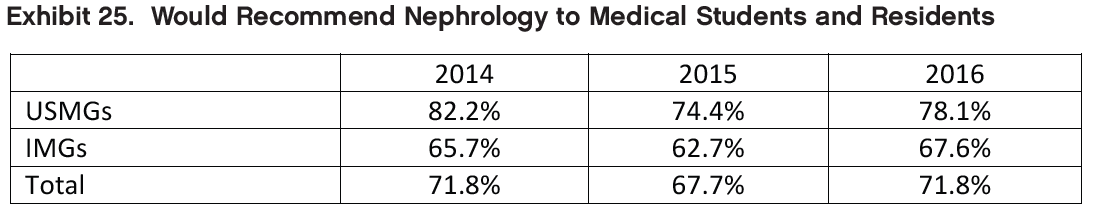

As in 2014 and 2015, most respondents (71.8%) said they would recommend the specialty to medical students and residents. Fellows recommending nephrology cited the field’s intellectual challenge, variety of activities, and patient relationships as reasons for their positive assessments. Fellows who would not recommend nephrology to medical students and residents cited the heavy workload, low compensation, difficult schedule, undervaluing of the specialty by other specialties, and lack of opportunities that support visas for IMGs as reasons for their negative assessments.

Overview of Respondents

The 315 respondents to the 2016 Nephrology Fellows Survey included fellows in their first and second year of their ACGME training program, as well as third-, fourth-, and fifth-year fellows in subspecialty training or research positions. Of the 315 respondents, 190 had completed at least 2 years of nephrology training; 131 had searched for a job; and 98 had accepted a job offer. Different sections of this report present findings on each of these groups of fellows. (The totals in each data table vary depending on the number of respondents who answered the particular question or questions being shown.)

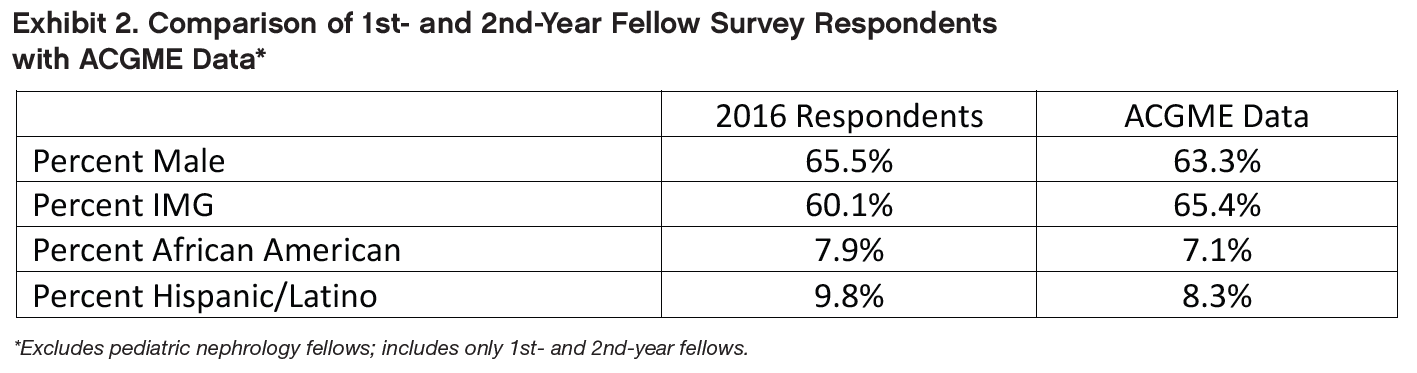

To assess the representativeness of the survey sample, we compared several demographic and educational characteristics of the 277 survey respondents in their first and second years of training to ACGME data on all 863 first- and second yearfellows. Respondents had very similar characteristics to all ACGME first- and second-year nephrology fellows, although the survey sample included slightly fewer IMGs and slightly more African American and Hispanic/Latino respondents. The percentages of African American and Hispanic/Latino survey respondents in their first and second years of training were higher in 2016 than in 2015—7.9% vs. 5.5% and 9.8% vs. 7.3% respectively.

Education, Citizenship Status, and Demographics of Respondents

This section presents data on the educational background, citizenship status, and demographics of all respondents to the 2016 Nephrology Fellow Survey.

Location of Medical School

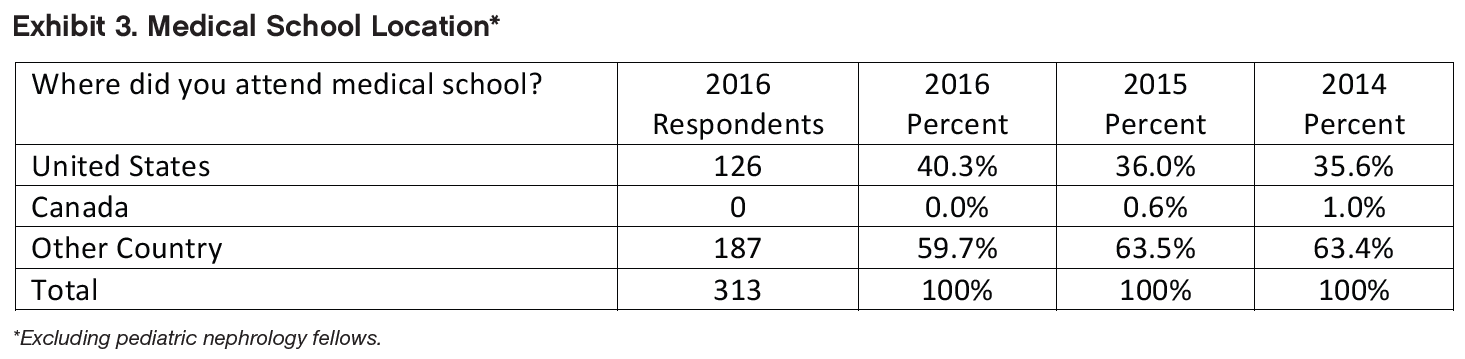

As in 2014 and 2015, most 2016 survey respondents (59.7%) attended medical school outside the United States. These IMG respondents reported attending medical school in 44 different countries, the most frequently cited of which were India (59 respondents), Mexico (11 respondents), Pakistan (10 respondents), Syria (7 respondents), Jordan, Lebanon and Nigeria (6 respondents each).

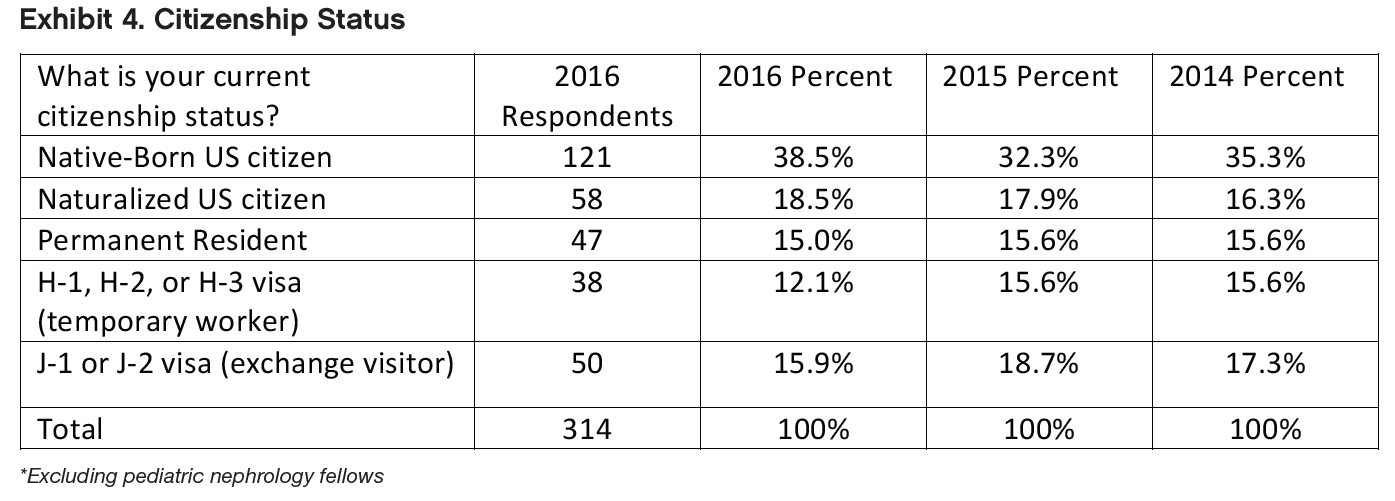

The distribution of 2016 survey respondents’ citizenship status was also similar to that of 2014 and 2015 respondents. More than half of 2016 respondents (57.0%) reported that they were US citizens, either native born or naturalized, and 15.0% reported that they were permanent residents of the United States. About 28.0% of the respondents were non-citizen holders of either H or J visas (a slightly smaller percentage than in 2015).

As in 2014 and 2015, we identified a small number of respondents who could be considered US IMGs, that is, US citizens who received their medical education outside the US. Fifteen respondents (8.1% of all IMGs who indicated their citizenship status) indicated that they were native-born US citizens who had received their medical education in another country.

Sex

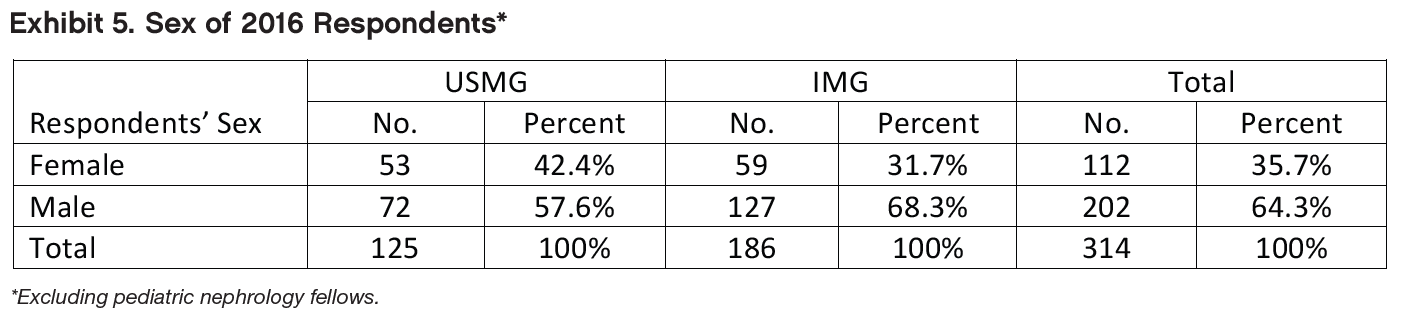

As in 2014 and 2015, the majority of 2016 survey respondents (64.3%) were male—a slightly larger percentage than in 2015 (59.7%). IMGs were more likely to be male (68.3% vs. 31.7% female), while the distribution among USMGs was more evenly balanced (57.6% male vs. 42.4% female)—but this difference was not statistically significant (unlike in 2015, when IMGs were significantly more likely to be male than USMGs).

Age

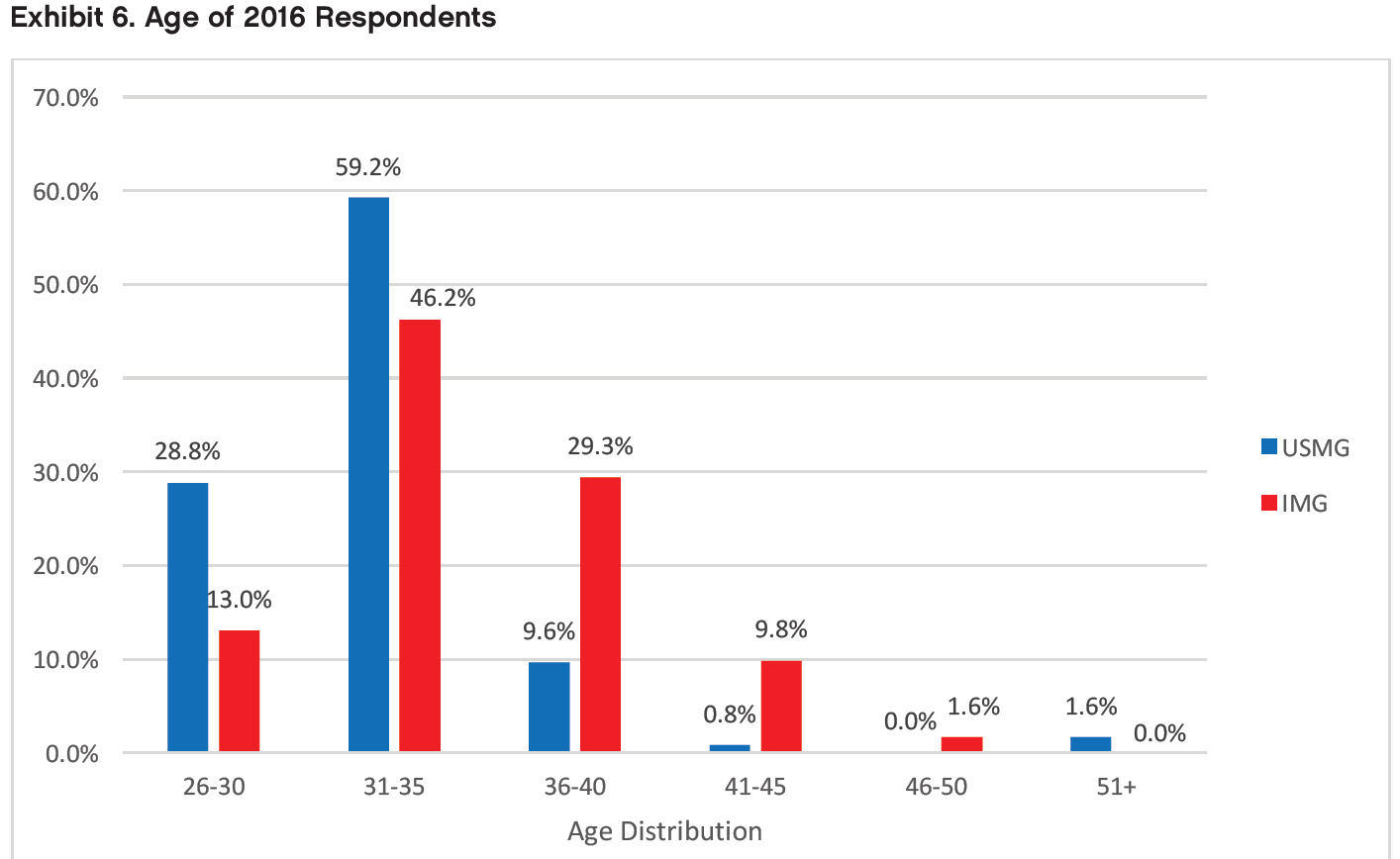

Respondents ranged in age from 28 to 62 years old. As in 2015, the largest age group was 31 to 35 years, which included more than one-half of respondents. Also, as in 2015, IMG respondents were significantly older on average than USMG respondents on average (35.0 years vs. 32.5 years—p<0.01).

Race/Ethnicity

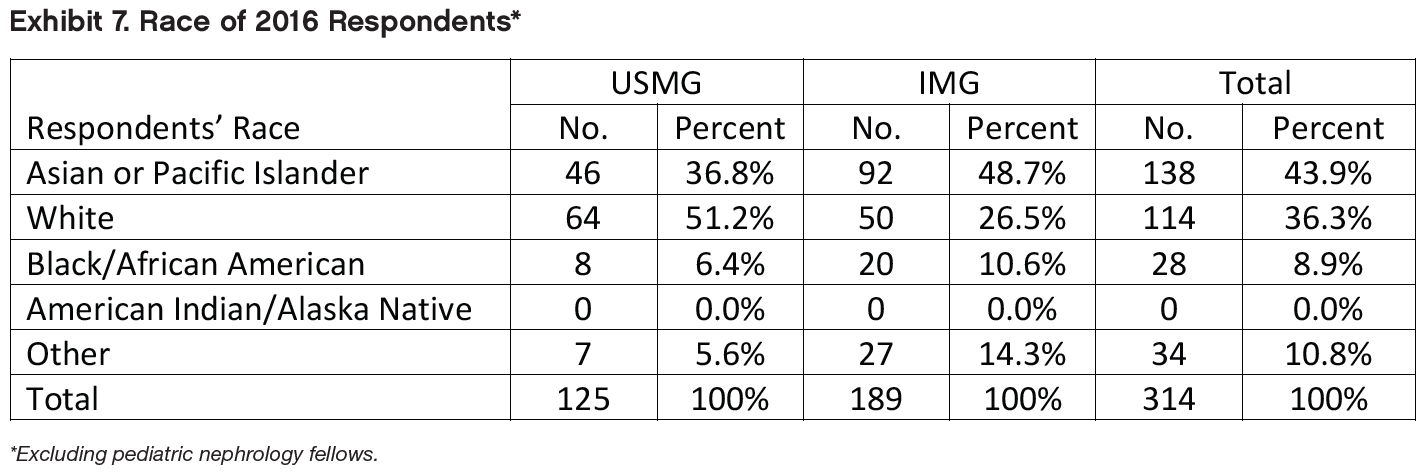

When asked to identify their race, the largest group of respondents identified themselves as Asian (43.9%), and the next largest group (36.3% of respondents) identified themselves as white. The distribution of race/ethnicity was significantly different across IMG categories: IMGs were significantly more likely to report being Asian (p<0.05) or of “other” race (p<0.05) than USMGs, and USMGs were significantly more likely to report being white than IMGs (p<0.01). The proportions of respondents who reported that they were black were not significantly different in the USMG and IMG groups.

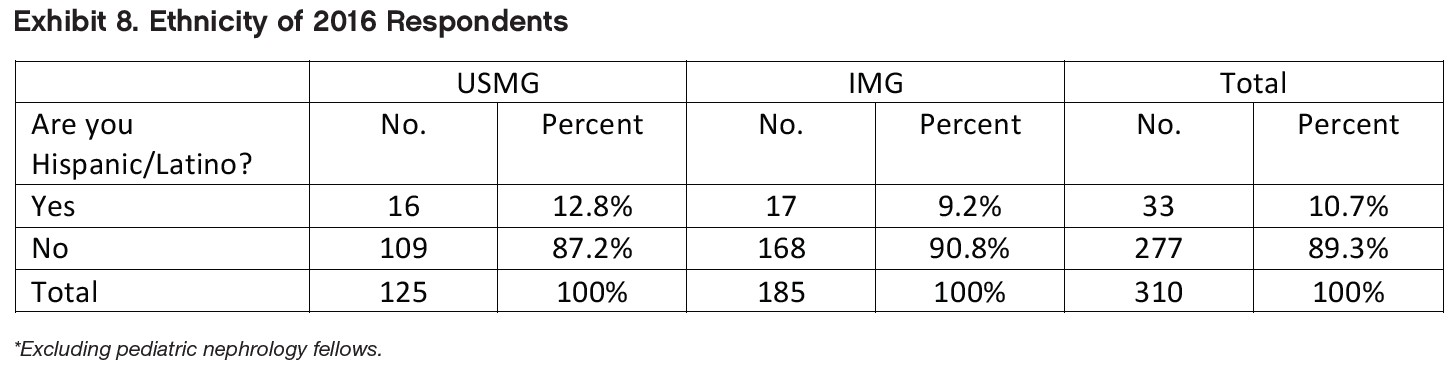

Nearly 11% of respondents identified themselves as Hispanic or Latino. This is higher than the 8.3% of ACGME residents and fellows who are Hispanic/Latino (Accreditation Commission for Graduate Medical Education, Annual Resource Data Book, 2015-16). IMG respondents were less likely to identify themselves as Hispanic or Latino than USMG respondents, but the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.35).

Educational Debt

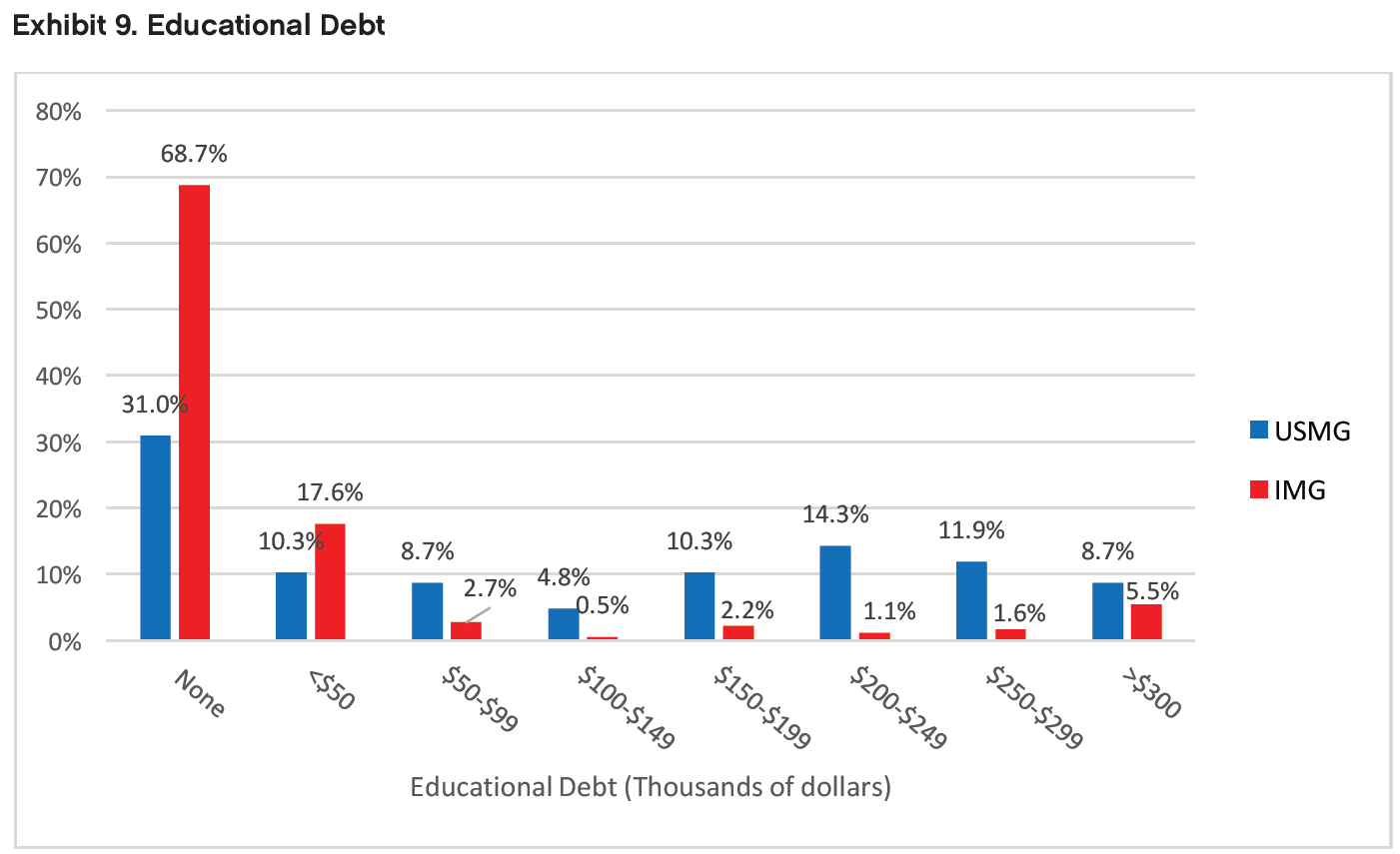

Respondents’ reported levels of educational debt varied from no debt to >$300,000. As in 2014 and 2015, IMGs were much less likely to be in debt than USMGs: 68.7% of IMG respondents reported having no educational debt compared with only 31.0% of USMGs (p<0.01). An additional 17.6% of IMGs reported educational debt levels <$50,000. USMG respondents were more likely than IMGs to report debt levels in every debt tier >$50,000. Almost 9% (8.7%) of USMG respondents and 5.5% of IMG respondents reported having >$300,000 of educational debt. IMG respondents had a median educational debt of $0, while USMG respondents had a median educational debt of between $75,000 and $124,999 (slightly lower than $125,000 and $149,999 in 2015).

Obligations to Practice in Underserved Areas

Excluding pediatric nephrology fellows and including only 2nd year and beyond. As in 2014 and 2015, the survey asked respondents if they had an obligation to work in an underserved area—either as part of a service-conditioned scholarship or loan repayment award for USMGs or a waiver of the requirement to return to their home country after training for IMG holders of J-1 training visas. The difference in the distribution of HPSA service obligations by IMG status was highly significant (p<0.01). While 48 IMGs (25.8%) indicated an obligation to work in a federally designated HPSA, only 1 (0.8%) USMG did so.

Post-Training Plans (2nd-Year and Beyond Fellows Only)

Activity After Completion of Current Training Year

Among respondents in their second year of fellowship or beyond who indicated their plans for the upcoming year (n=190), the largest percentage planned to enter clinical nephrology practice (55.8%). The next largest groups (13.7% each) intended to continue in their current fellowships or pursue additional subspecialty training. Among the 52 fellows who planned to continue their training (either through additional subspecialty training or by continuing in their current fellowships), the largest groups said they planned to pursue training in research (48.1% [25 respondents]) and transplant nephrology (34.6% [18 respondents]). A smaller group (7.7% [4 respondents]) said they planned to pursue training in interventional nephrology. Other types of training respondents mentioned included critical care, clinical nutrition, and glomerular disease.

We found a significant difference in the distribution of anticipated activities between USMG and IMG fellows (p<0.01): IMGs were more likely to report pursuing additional subspecialty training (19.1% vs. 6.4%) and entering teaching/research positions (12.7% vs. 9.0%), and USMGs were more likely to report that they planned to continue their current fellowships (25.6% vs. 5.5%).

We found no significant difference in the distribution of anticipated activities between male and female fellows (p=0.71).

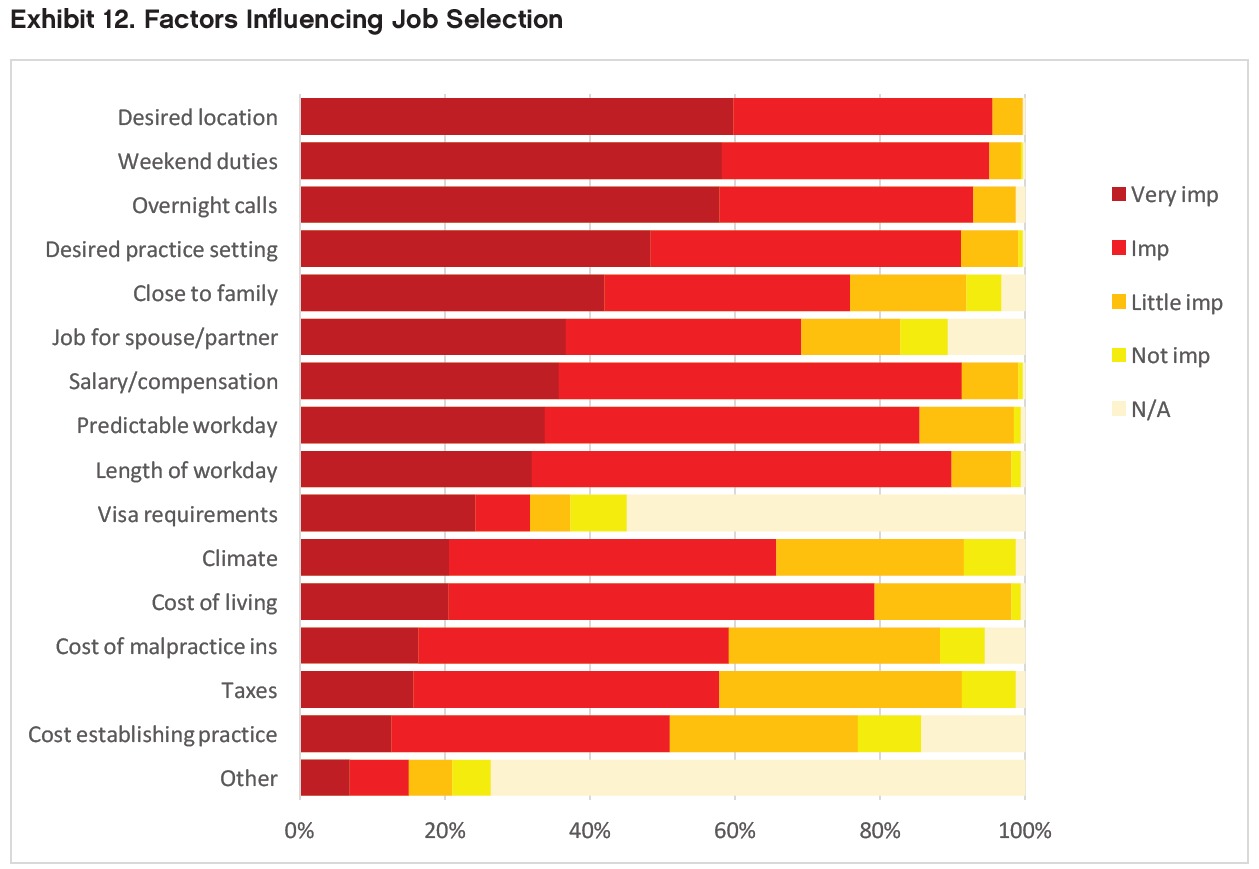

Factors Influencing Job Selection

Respondents in their second year of fellowship or beyond rated the following factors as very important or important in their job selection:

Job/practice in desired location (95.5% very important or important)

Frequency of weekend duties (95.1%)

Frequency of overnight calls (92.9%)

Job/practice in in desired practice setting (91.2%)

Salary/compensation (91.2%)

Length of each workday (89.9%)

They rated the following factors as least important:

Cost of malpractice insurance (59.2% very important or important)

Cost of living (58.8%)

Taxes (57.8%)

Cost of setting up a medical practice (51.0%)

Job/practice meets visa requirements (31.7%)

USMGs and IMGs differed significantly when rating the following factors:

Job/practice meets visa requirements (IMGs more likely than USMGs to rate as very important or important, p<0.01)

Length of each workday (IMGs more likely than USMGs to rate as very important, p<0.05)

Salary/compensation (IMGs more likely than USMGs to rate as very important, p<0.05)

Climate/weather (IMGs more likely than USMGs fellows to rate as very important, p<0.05)

USMG and IMG fellows’ ratings of other factors were not significantly different.

Male and female fellows differed significantly when rating the following factors:

Job/practice in desired setting (female fellows more likely than male fellows to rate as very important or important, p<0.05)

Length of each workday (female fellows more likely than male fellows to rate as very important, p=0.05 [approaches statistical significance])

Employment opportunities for spouse/partner (female fellows more likely than male fellows to rate as very important or important, p<0.05)

Male and female fellows’ ratings of other factors were not significantly different.

Job Market Experiences and Perceptions

This section reports on the experiences of the 131 nephrology fellows who had searched for employment. As in 2015, the job market was challenging, especially for IMG fellows who were more likely than USMG fellows to report applying for large numbers of jobs, having difficulty finding a satisfactory position, and changing plans because of limited opportunities.

Number of Job Applications

Among fellows who had searched for a job, 58.0% reported applying for between 1 and 5 jobs, and 35.9% reported that they had applied for at least 6 jobs (including 19.9% who applied for more than 10 jobs). A few fellows (6.1%) reported that they had not applied for any jobs.

We found a statistically significant difference in the number of job applications between IMG and USMG fellows (p<0.01): IMGs were more likely than USMGs to apply for more than 10 jobs (29.6% vs. 4.0%), and USMGs were more likely than IMGs to apply for 1 or 2 jobs (36.0% vs. 21.0%). The percentage of USMGs who reported that they applied for 5 or more positions declined from 43.5% in 2015 to 34.0% in 2016 (still greater than 28.6% in 2014). The percentage of IMGs who reported applying for 5 or more jobs held roughly steady at 61.7% (vs. 63.3% in 2015—still greater than 47.4% in 2014).

We found no statistically significant differences existed in the number of job applications between male and female fellows (p=0.18).

Among these, 29.6% reported applying to more than 10 positions. The percentage who reported receiving no job offers declined slightly from around 10% in 2014 and 2015 to 6.2% in 2016.

Number of Job Offers

The majority of nephrology fellows (63.4%) reported receiving between 1 and 3 job offers. A small number of fellows reported receiving more than 10 job offers (2.3%), and 5.3% of fellows reported receiving no job offers. The percentage of USMGs who reported receiving no job offers (4.0%) was similar to 2015 (3.8%).

We found a statistically significant difference in the number of job offers between IMG and USMG fellows (p<0.05). USMGs were more likely to report receiving 1 to 3 job offers (80.0% vs. 53.1%), and IMGs were slightly more likely to report receiving no job offers (6.2% vs. 4.0%). On the other hand, all of the fellows who received over 10 job offers were IMGs.

We found no statistically significant differences in the number of job offers between male and female fellows (p=0.94).

Difficulty Finding a Satisfactory Position

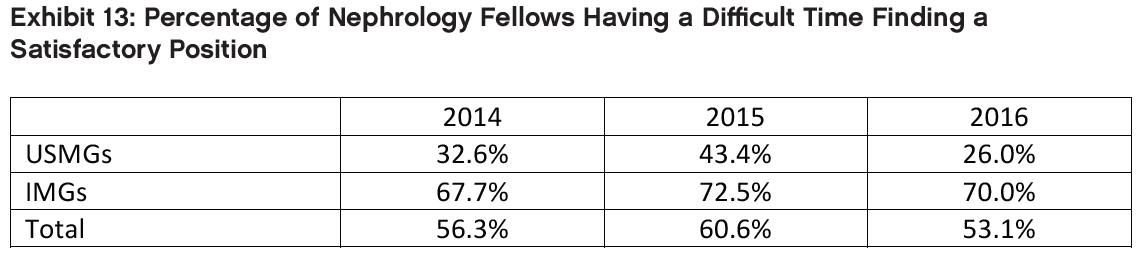

A majority of respondents (53.1%) who had searched for jobs reported having difficulty finding a satisfactory position (Exhibit 13). We found a statistically significant difference between IMG and USMG fellows’ reports of difficulty finding a position (p<0.01): while 70.0% of IMGs reported having difficulty finding a position they were satisfied with, only 26.0% of USMGs reported having difficulty. For USMGs, there was a major improvement between 2015 and 2016 with the percent reporting a difficult time dropping from 43.4% in 2015 to 26% in 2016.

We found no statistically significant difference in reports of difficulty finding a position between male and female fellows (p=0.91).

Reasons for Difficulty

Among the fellows who reported difficulty finding a satisfactory position, the top 3 most frequently cited reasons were consistent from 2015 to 2016. The reasons most frequently cited by 2016 fellows were lack of jobs/ practice opportunities that meet visa status requirements (27.5%), lack of jobs/practice opportunities in desired locations and inadequate salary/compensation (26.1% each).

We found a statistically significant difference in reasons for difficulty finding a position between IMG and USMG fellows (p<0.01). IMGs were more likely than USMGs to cite lack of jobs that meet visa requirements (33.9% vs. 0%) and inadequate salary/compensation (28.6% vs. 15.4%). USMGs were more likely than IMGs to cite overall lack of jobs (23.1% vs. 1.8%) and lack of jobs in desired locations (38.5% vs. 23.2%). (In 2015 IMGs were more likely to cite lack of jobs in desired locations and USMGs were more likely to cite inadequate salary/compensation.)

We also found no statistically significant difference in the reasons for difficulty finding a position between male and female fellows (p=0.69).

Changing Plans Due to Limited Practice Opportunities

Overall, the percentage of respondents indicating that they had changed their plans because of limited nephrology job opportunities declined slightly, from 42.9% in 2015 to 35.4% in 2016. While both USMGs and IMGs were less likely to report changing their plans in 2016 than in prior years, their likelihood of changing plans was significantly different: only 16.0% of USMGs reported that they had to change plans, while 47.5% of IMGs reported changing plans (p<0.01). This difference likely reflects a continuing lack of job opportunities that meet visa requirements while allowing IMGs to practice in their preferred locations or settings.

We found no statistically significant differences in male and female fellows’ likelihood of changing their plans (p=0.91).

Job Market Perceptions

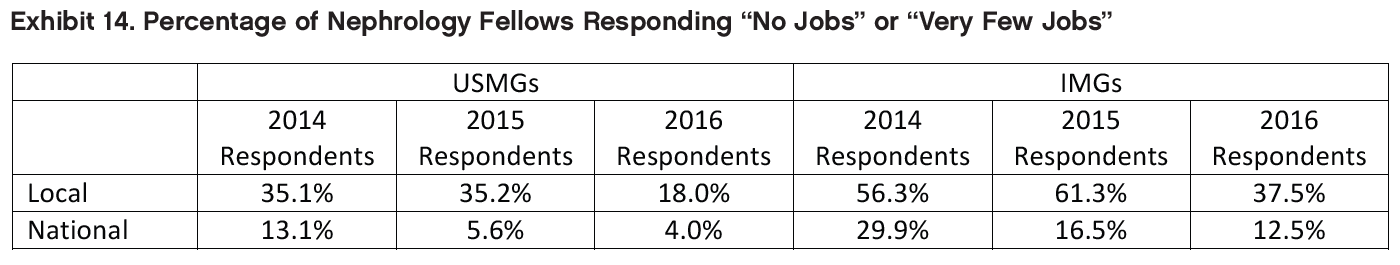

Survey respondents were asked to indicate their perceptions of the local job market (within 50 miles of where they trained) and the national job market. Response options ranged from no jobs to many jobs. Key findings include:

Perceptions of the local and national job markets were more positive in 2016 (vs. 2014 and 2015) for both USMGs and IMGs;

As in 2014 and 2015, the 2016 fellows were more likely to indicate that there were few or no job opportunities in the local job market compared to the national market; and

As in 2014 and 2015, USMGs had a far more favorable view of the local and national markets than IMGs.

Local Job Market Perceptions

Among nephrology fellows who had searched for jobs, perceptions of local nephrology job opportunities were improved since 2015: while 24.6% reported that there were many or some nephrology practice opportunities within 50 miles of their training sites in 2015, the proportion reporting the same in 2016 increased to 37.7%.

We found a statistically significant difference in IMG and USMG fellows’ assessments of local nephrology practice opportunities (p<0.05): USMGs were more likely than IMGs to report that there were many or some job opportunities in their local area (56.0% vs. 26.3%).

We found no statistically significant differences in local job market perceptions between male and female fellows (p=0.51).

National Job Market Perceptions

Nephrology fellows perceived national nephrology job opportunities much more positively than local opportunities: 63.0% reported there were some or many nephrology practice opportunities nationally (a slight improvement from 57.9% in 2015).

We found no statistically significant difference in IMG and USMG fellows’ assessments of national nephrology practice opportunities (p=0.25) or between male and female fellows (p=0.34).

Types of Jobs Available

When we asked fellows to indicate in an open-ended question what types of jobs they perceived to be more and less available for newly graduating fellows, they mentioned several types of jobs that were more easily available according to their experience:

Private practice jobs

Jobs in remote, rural or undesirable areas (e.g., Midwest, South)

Jobs in small practices/hospitals/communities

They also mentioned several types of jobs that were less easily available according to their experience:

Academic jobs

Jobs in metro areas or other preferred geographic areas (e.g., Florida, California, Pacific Northwest)

Jobs that meet visa requirements for IMGs

Job Offer Characteristics

Among the 98 nephrology fellows who had already accepted job offers, we found the following with respect to their salary and compensation expectations.

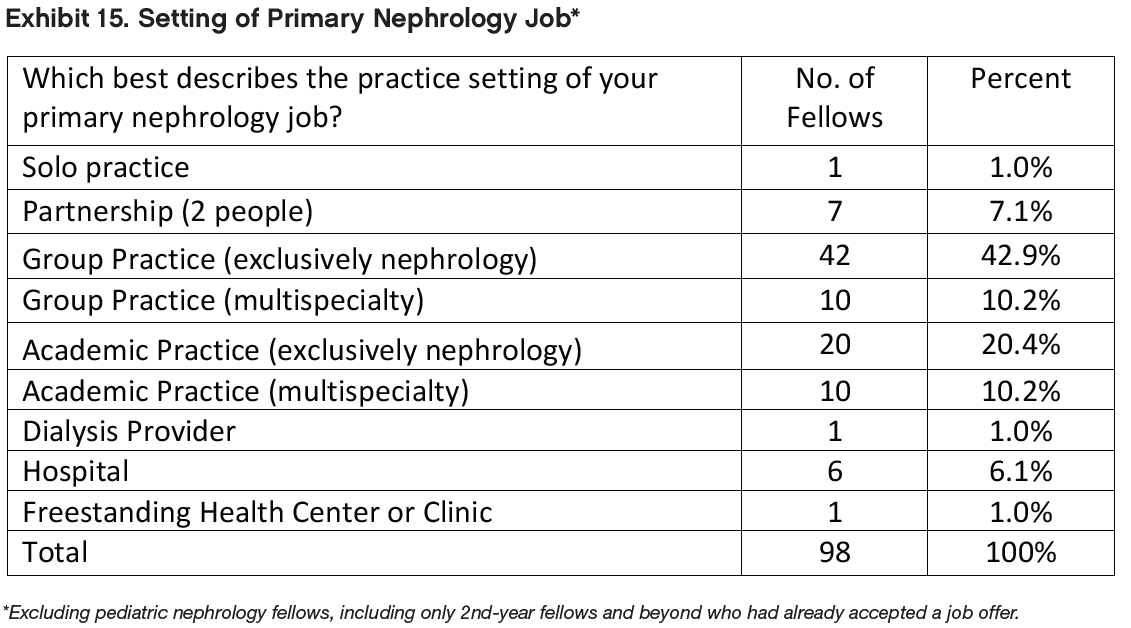

Practice Setting

Among respondents who had already accepted job offers, the largest group (42.9%) reported that they planned to work in nephrology group practices. Another 20.4% reported that they planned to work in academic nephrology practices, and 10.2% each said they planned to work with multispecialty group practices and academic multispecialty practices. Other settings included 2-person partnerships (7.1%) and hospitals (6.1%).

The distribution of patient care settings between male and female fellows approached statistical significance (p=0.05). Female fellows were more likely to report that they planned to work in academic nephrology (27.0% vs. 16.4%), multispecialty practices (18.9% vs. 4.9%), and hospitals (10.8% vs. 3.3%); and male fellows were more likely to report that they planned to work in nephrology group practices (47.5% vs. 35.1%) and multispecialty group practices (14.8% vs. 2.7%).

Location of Practice

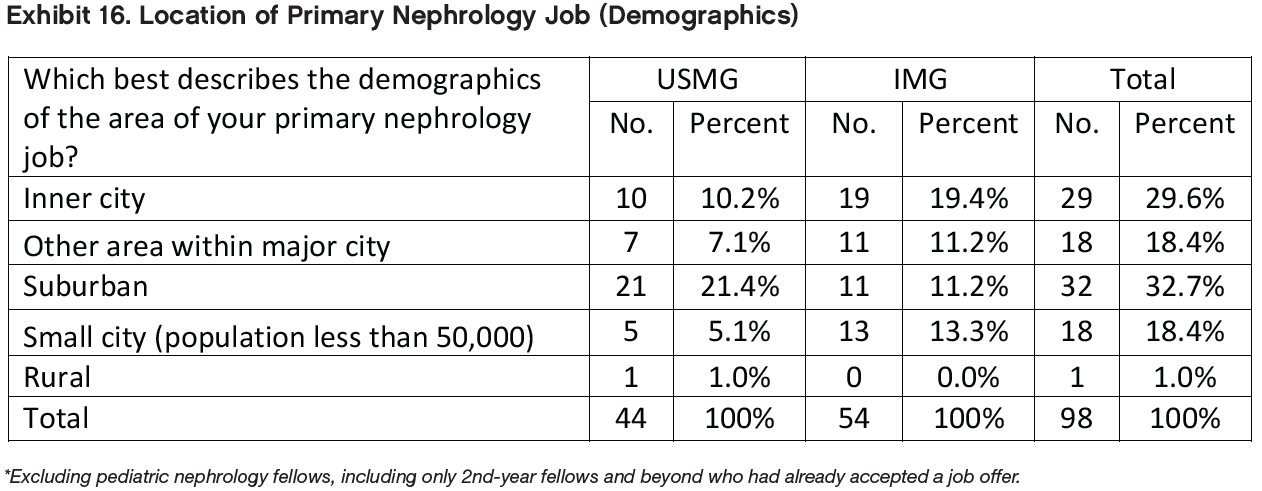

Among respondents with job offers, almost half (48.0%) indicated that they planned to work in urban areas (inner city or other). Another 32.7% said they planned to work in suburban areas, and 18.4% said they planned to work in small cities. Only one fellow (1.0% of respondents) reported intending to work in a rural area despite the fact that many respondents had indicated that jobs were more readily available there.

The distribution of practice locations was significantly different for USMGs and IMG fellows (p<0.05). USMGs were more likely to report intending to work in suburban areas (47.7% vs. 20.4%), while IMGs were more likely to report intending to work in inner cities (35.2% vs. 22.7%), other urban areas (20.4% vs. 15.9%), and small cities (24.1% vs. 11.4%). The single respondent who indicated an intention to work in a rural area was a USMG.

We found no statistically significant differences between male and female fellows’ anticipated practice locations (p=0.36).

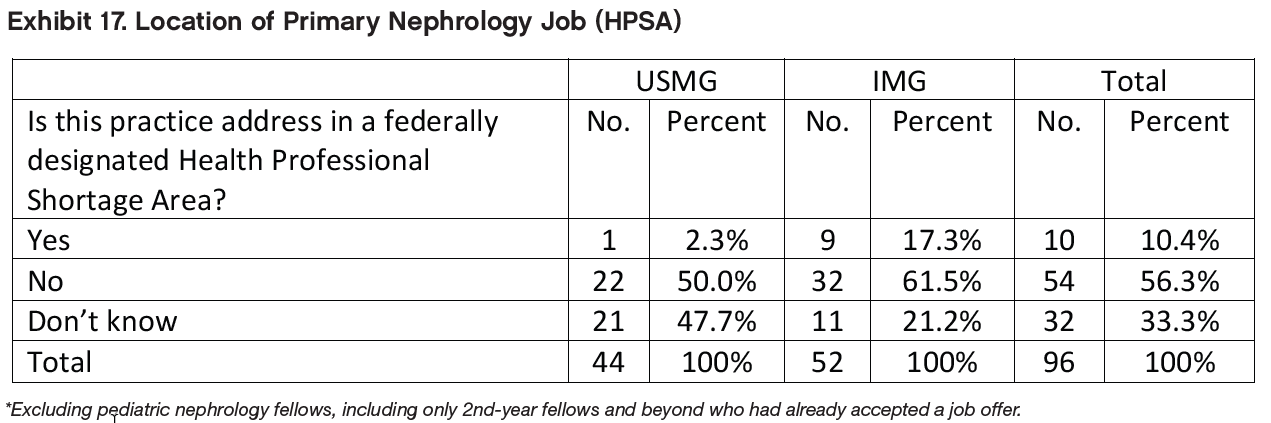

Among the 96 respondents who indicated whether their job offers were located in a HPSA, 10.4% (10 respondents) reported their principal practice address was in a HPSA. (One third of this group [33%] did not know, and the rest [56.3%] said no.) Among the 10 respondents who planned to work in a HPSA, 9 were IMGs. The difference in distribution of IMGs’ and USMGs’ practice locations was statistically significant (p<0.01).

We found no statistically significant differences between male and female fellows’ intentions to practice in a HPSA (p=0.95).

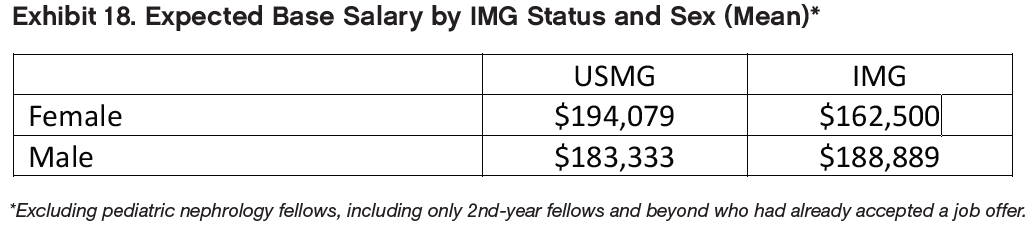

Base Salary/Income

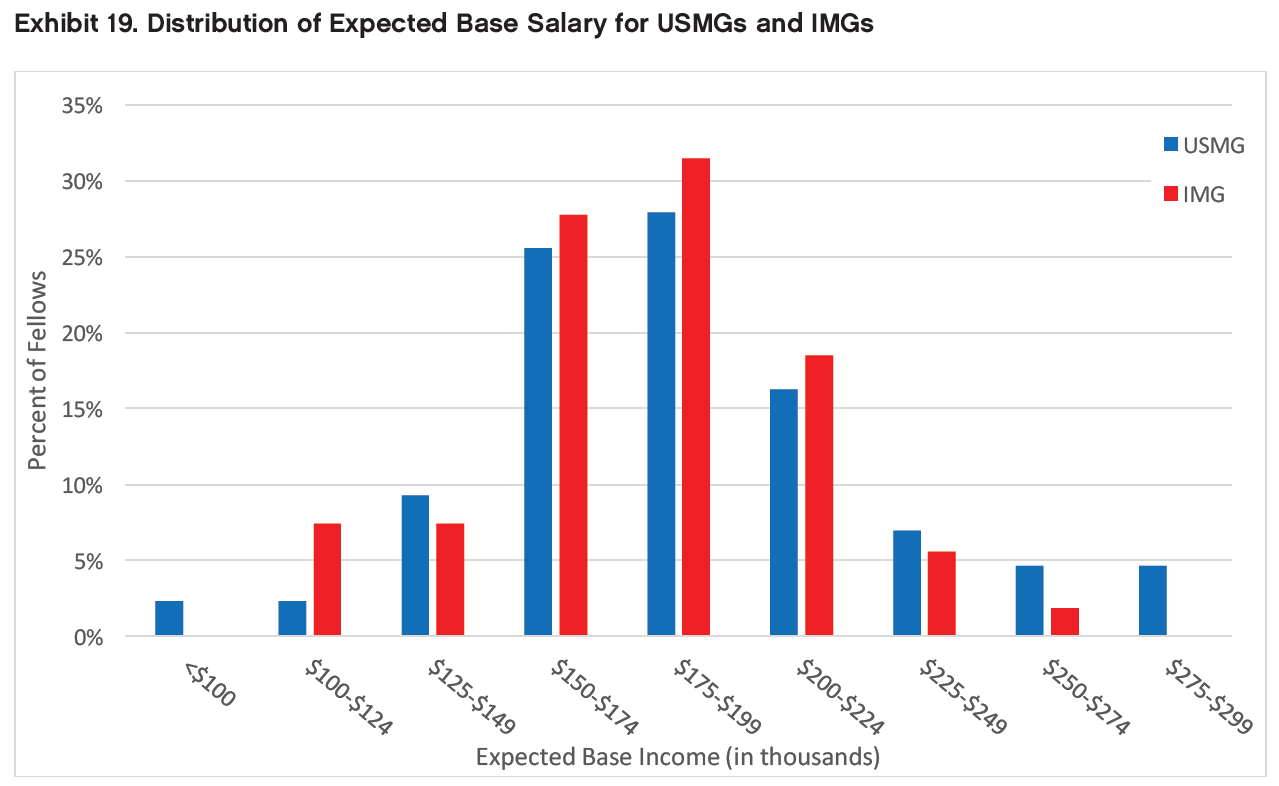

Among the fellows who had accepted job offers, the range of expected salaries was from <$100,000 to $299,999. More than half (56.7%) anticipated annual base salaries between $150,000 and $199,999.

As in 2015, mean and median expected base salaries for all demographic groups (by IMG status and gender) all fell into the $175,000 to $199,999 range (except mean income for female IMG fellows, which was slightly but not significantly lower). (Because survey respondents were only asked to report their salaries within $25,000 ranges, the calculation of mean values set out in Exhibit 18 relies on the assumption that actual salaries were evenly distributed within each salary range, which is by no means guaranteed.)

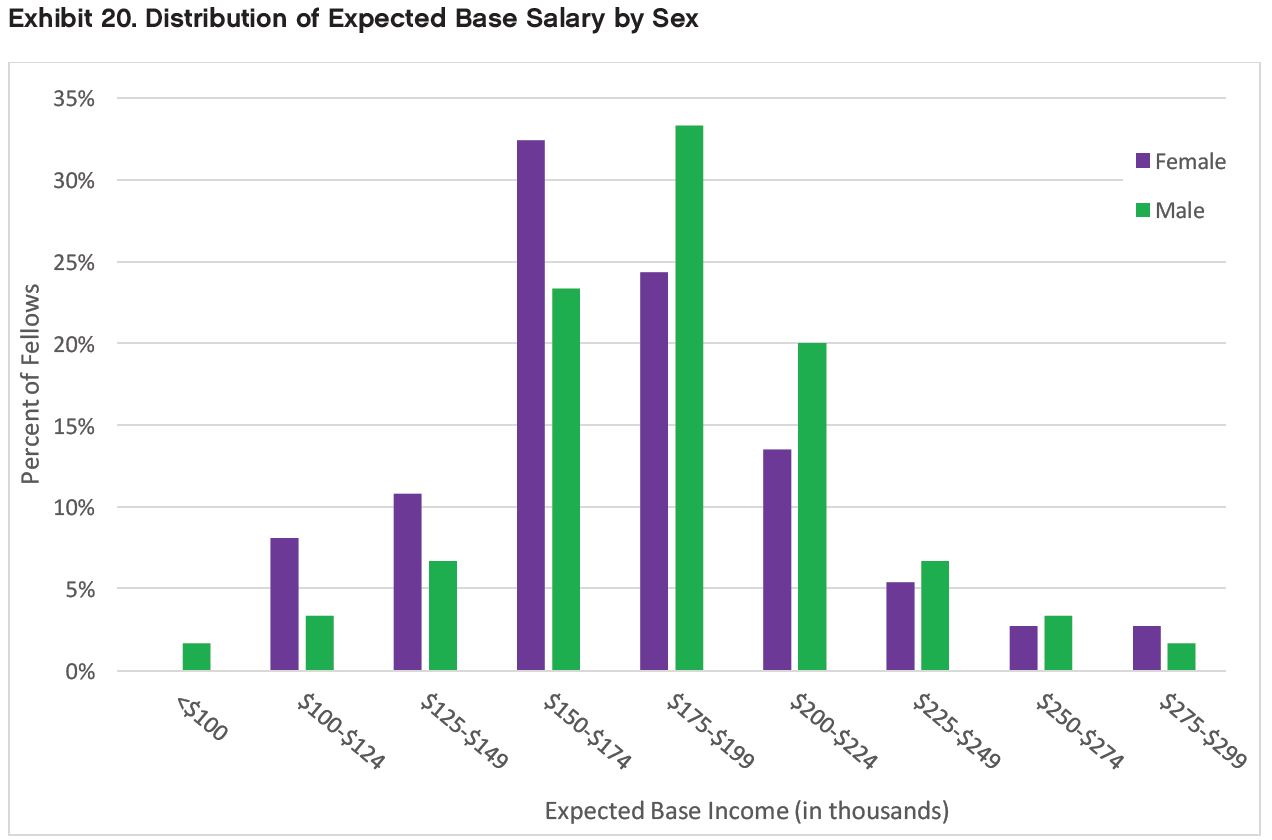

Exhibits 19 and 20 show fellows’ expected base salaries in histogram form. In the histograms the pattern of IMG vs. USMG differences is not consistent across the salary range, and the overall distribution of expected salaries was not significantly different between IMGs and USMGs (p=0.75). Male fellows tended to report higher base salaries than female fellows across virtually the entire range of reported salaries, with more males than females in ranges above $175,000 and more females than males in ranges below $175,000. However, this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.85).

Anticipated Additional Incentive Income

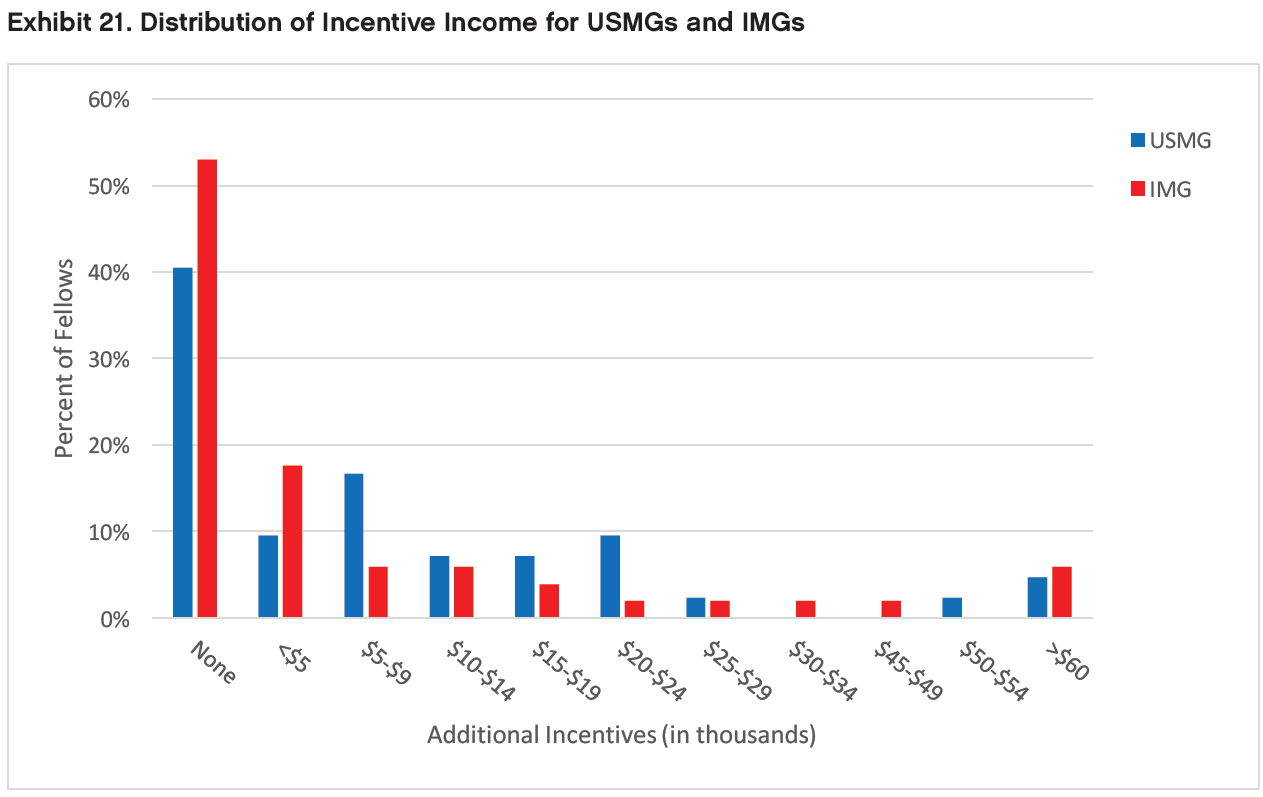

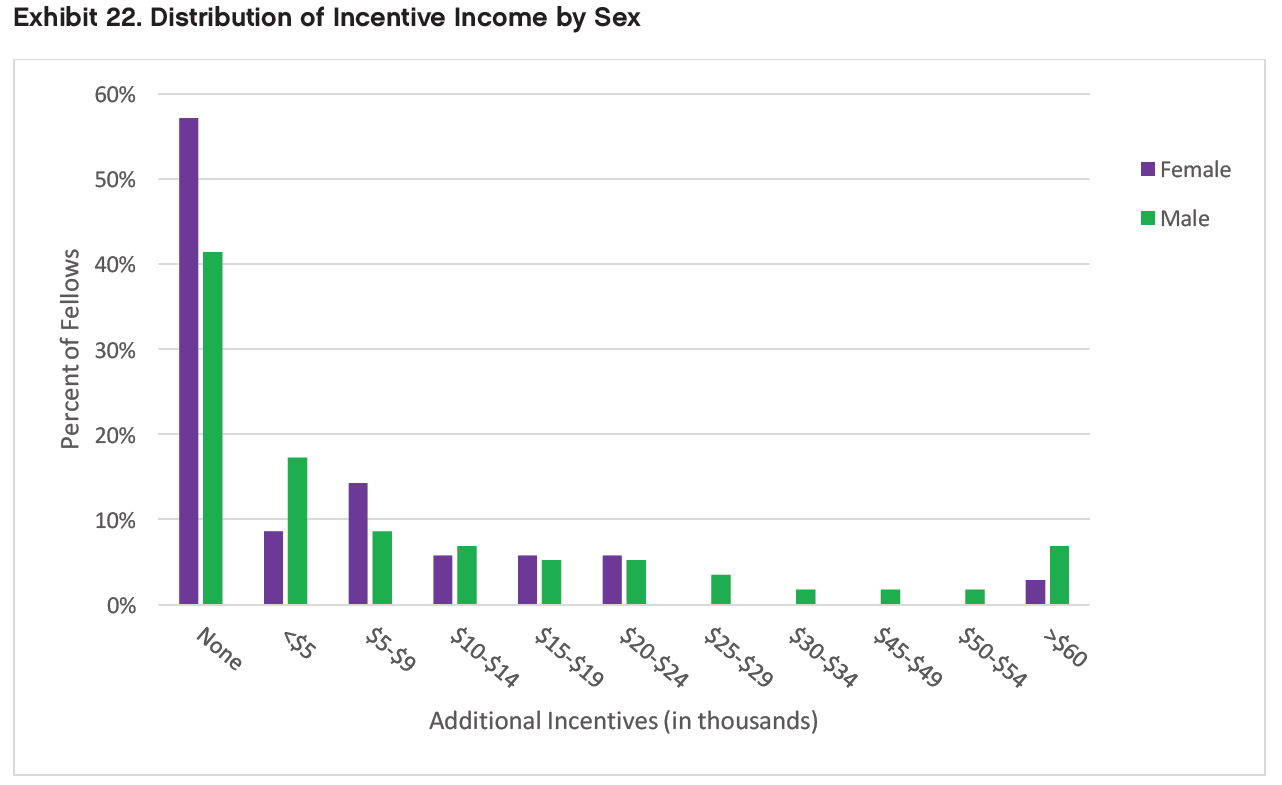

Nearly half (47.3%) of fellows who had accepted job offers did not anticipate receiving any additional incentive income. Among those expecting to receive incentive income, most reported that they expected to earn <$10,000, although the range of expected incentives extended to >$60,000 for five fellows. (Only a single respondent reported incentive income this high in 2015.)

Exhibits 21 and 22 show fellows’ expected incentive income in histogram form. We found no significant differences in expected incentive income between IMGs and USMGs (p=0.40) or male and female fellows (p=0.87).

Secondary Jobs

Among the respondents who had accepted nephrology jobs, 23 indicated that they planned to take on a second nephrology job in addition to their primary job. The majority (14 respondents [60.9%]) planned to take medical directorships with dialysis providers. Other types of secondary jobs included hospital care (7 respondents [30.4%]), moonlighting in non-nephrology inpatient units (6 respondents [26.1%]), joint ventures with dialysis providers (5 respondents [21.7%]), and moonlighting in nephrology inpatient units (2 respondents [8.7%]).

Among fellows who reported their expected income from secondary nephrology jobs, more than half (63.2%) expected to earn <$25,000 in their secondary jobs. While this was similar to 2015, the upper end of the secondary job income range was higher in 2016: expected income from secondary nephrology jobs ranged up to $100,000 or more (2 respondents) vs. only $25,000-$49,999 in 2015.

Income Comparisons

Using the income calculation methodology detailed in the previous report, we conducted statistical comparisons of mean anticipated incomes between IMGs/USMGs and male/female fellows. We found no statistically significant differences for either comparison (p=0.27 and p=0.16 respectively). We also compared mean anticipated incomes between fellows planning to work in different practice locations (e.g. inner cities, suburban areas, etc.) and found no statistically significant difference between different practice locations (p=0.57).

We found a statistically significant difference between mean anticipated incomes between different practice settings (p<0.01): fellows planning to work in academic nephrology ($156,875), nephrology group practice ($184,756) and 2-person partnerships ($187,500) had the lowest mean anticipated incomes, while fellows planning to work in solo practice and freestanding health centers ($275,000 each), multispecialty group practices ($247,500) and hospitals ($237,083) had the highest mean anticipated incomes. (These findings should be interpreted with caution, as the solo practice and freestanding health center categories had one respondent each and thus were not included in the statistical test.)

Satisfaction with Salary/Compensation

The majority of fellows who had accepted job offers indicated they were satisfied with their salary and compensation. Approximately 31.6% reported being “very satisfied,” and 40.8% indicated that they were “somewhat satisfied” with their salary and compensation. We found a statistically significant difference in satisfaction with salary and compensation between IMGs and USMGs (p<0.05). USMGs were more likely to report being “very satisfied” with their salary and compensation (47.7% vs. 18.5%), and IMGs were more likely to report being “very dissatisfied” (11.1% vs. 4.6%).

We also found a statistically significant difference in satisfaction with salary and compensation between male and female fellows (p<0.05). Female fellows were more likely to report being “very satisfied” with their salary and compensation (48.7% vs. 21.3%), and male fellows were more likely to report being “somewhat satisfied” (49.2% vs. 27.0%) and “somewhat dissatisfied” (21.3% vs. 16.2%).

Incentives

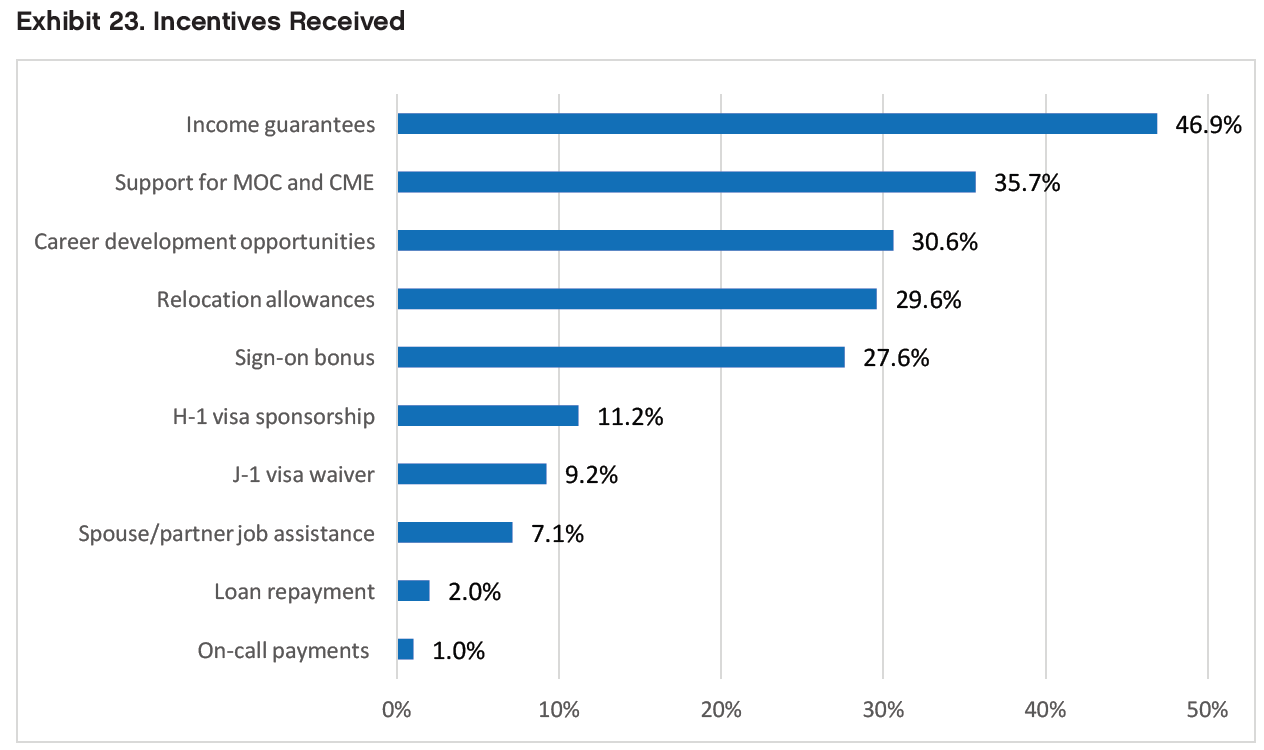

When asked to identify the incentives they had received for accepting their primary job offers, respondents were most likely to report receiving the following:

Income guarantees (46.9%)

Support for MOC and CME (35.7%)

Career development opportunities (30.6%)

Relocation allowances (29.6%)

Sign-on bonus (27.6%)

On-call payments (1.0%) and educational loan repayment (2.0%) were the least frequently reported incentives. Another 11.2% of respondents who had accepted jobs reported receiving no incentives.

Not surprisingly, we found statistically significant differences between IMG and USMG respondents’ reports of receiving H-1 visa sponsorship (p<0.01) and J-1 visa waivers (p<0.01). IMGs’ and USMGs’ reports of receiving other incentives were not significantly different from each other. We found no statistically significant differences between male and female respondents’ reported incentives.

Among respondents who reported receiving incentives with their primary job offers, more than half (59.3%) reported that they were “important” or “very important” in their decision to accept the job. We found a statistically significant difference between IMGs’ and USMGs’ ratings of the importance of the incentives they had received (p<0.05). IMGs were more likely than USMGs to rate the incentives they had received as “important” or “very important” (68.8% vs. 45.5%).

We found no statistically significant differences between male and female respondents’ ratings of the importance of the incentives they had received (p=0.26).

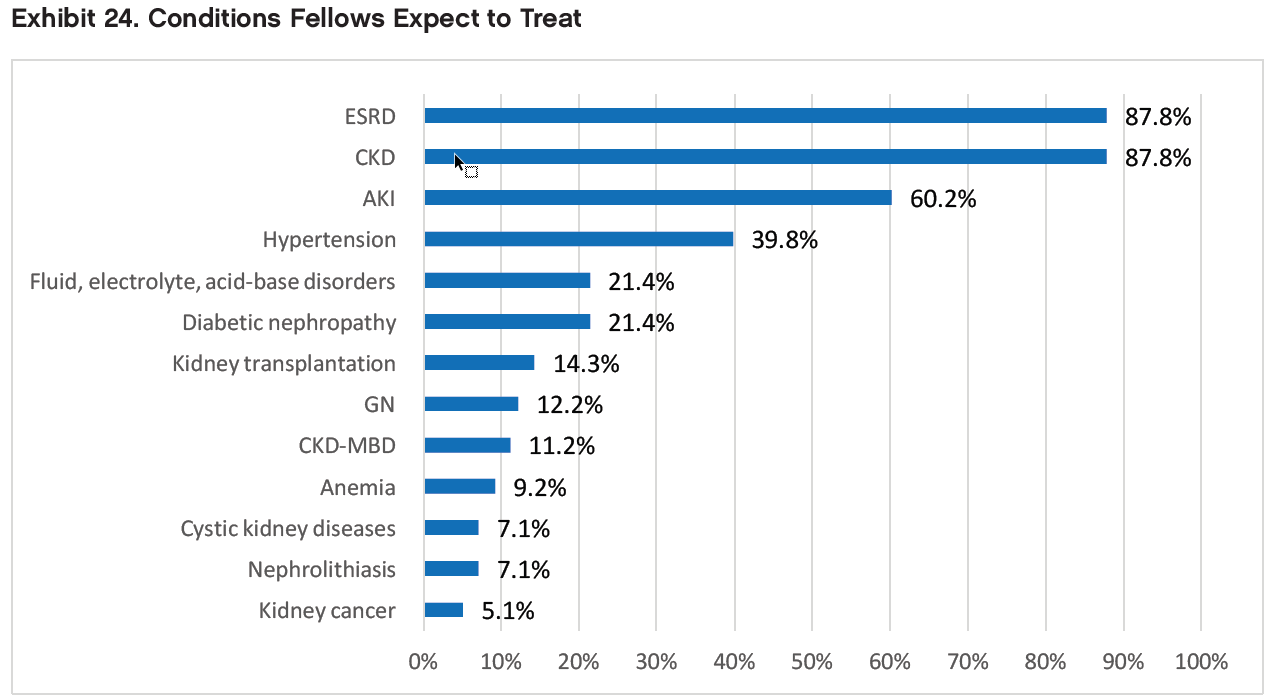

Conditions Fellows Expect to Treat

When asked to identify the top 3 conditions they expected to treat in their practice (both primary and secondary jobs), respondents who had accepted job offers most frequently cited CKD (87.8%), ESRD (87.8%), AKI (60.2%), and hypertension (39.8%)—the same conditions as in 2015. The least frequently expected conditions were nephrolithiasis (7.1%), cystic kidney diseases (7.1%), and kidney cancer (5.1%)—also the same as in 2015.

Among dialysis modalities, respondents who had accepted job offers were most likely to expect to work with in-center hemodialysis (100%), followed by home peritoneal dialysis (72.6%), and home hemodialysis (47.4%). A much smaller group (13.7%) said they anticipated working with nocturnal in-center hemodialysis.

Would Fellows Recommend Nephrology?

Despite their mixed assessments of the nephrology job market, a majority (71.8%) of fellows indicated they would recommend nephrology to current medical students and residents. However, IMGs were significantly less likely than USMGs to report that they would recommend the specialty to others (67.6% vs. 78.1%, respectively, p=0.05). We found no statistically significant difference between male and female fellows’ likelihood of recommending nephrology (p=0.51).

Fellows who said they would recommend nephrology to medical students and residents cited many of the same factors mentioned by 2015 respondents as reasons for their positive assessments: the intellectual challenge/ interest of the field, variety of activities, and long-term patient relationships.

Fellows who said they would recommend nephrology to medical students and residents made the following comments to support their assessments:

“The reason I pursued a career in medicine is to be able to create longstanding relationships with patients and be a part of their lives as we grow to trust each other over time. With nephrology I’m already seeing how strong these bonds can be with chronic clinic patients and ESRD patients. Additionally, I followed my interest in nephrology because of how stimulating it is to problem solve and apply math and physiology to acid base disorders, electrolyte disorders and even acute kidney injury. Money and debt matter, but all fields of medicine will provide a comfortable and rewarding lifestyle financially. Nephrology will allow me to continue to be awed by medicine and the human body every day which helps me to enjoy each new challenging day at work.”

“Nephrology is one of few medicine subspecialties that allow you to function almost as a primary caregiver for your patients. For example, as a nephrologist, you will see your dialysis patients much more often than their PMD and therefore have an increased opportunity to forge a lasting relationship with them. Furthermore, nephrology is a unique subspecialty in that nephrologists must truly be able to recognize and comprehend whole body pathophysiology, as a decline in one organ system almost always has a deleterious effect on renal function. I think if medical students and residents are interested in continuity of care and establishing long-lasting physician-patient relationships without the onus of being a patient’s primary care provider, nephrology is good match.”

“Nephrology is an underrated specialty marred by comparatively poor salaries. I find dealing with electrolyte imbalances and volume challenges very exciting. I also think we suffer from poor investment in research which has not lead to pathbreaking discoveries for instance as in oncology, cardiology or hepatology. To increase student and resident interest, I believe rotations should include one day a week in the outpatient dialysis clinic to add flavor to the overall experience. We are very diverse and we need to show it off.”

“Kidneys [are the] second smartest organ next to brain, some may say smartest organ. Nephrology is not only dialysis—it’s about whole body physiology. Well, we even don’t know how to effectively find solutions for challenges in hemodialysis. Lot of basic science and art of physiology, but unfortunately it is seen and postulated during medical school/residency training as field of dialysis, field where you work hard and get less money. [The latter] part is unfortunately true. Even other fields of medicine consider nephrology as dialysis, and do not understand physiology and put catheters to start dialysis. Cardiology and pulmonary fields have to realize that nephrologists are the expert in making the decision when, where and who to dialyze. Unfortunately it’s [a] nationwide problem.”

“If you have a deep love for physiology and understanding the mechanics of the body, nephrology training cannot be beat. It will make you a better doctor, even if you choose not to remain a nephrologist. The level of complexity both acute and chronic is not really seen in other patient populations. It’s rigorous and challenging. The problem is it feels like there’s no way to do a good job. But maybe all doctors feel that way?”

One fellow who recommended the specialty nonetheless offered the following caveats about private practice nephrology (compared with academic nephrology):

- “I believe that academic nephrology is fulfilling. However, I would not recommend private practice nephrology. I was actually a private nephrology practitioner for 3 years before I completed a transplant nephrology fellowship. There is too much traveling and too much economic focus in private practice. The call schedule is also much less desirable in private practice compared to academics. The focus is mostly on billing and on seeing high numbers of patients rather than on quality of care and on learning.” Fellows who said they would not recommend nephrology to medical students and residents also cited many of the same factors as in 2015: the heavy workload, low compensation, difficult schedule relative to hospital medicine and other specialties, undervaluing of the specialty by other specialties, and lack of opportunities that support visas.

Fellows who said they would not recommend nephrology to medical students and residents made the following comments to support their assessments:

“If they are on a visa I would be very reluctant to recommend nephrology. No matter how qualified and how excellent your training ends up being, as an IMG on a visa you will end up working for 3-5 years in a community doing primary care or hospitalist to meet the waiver requirements. No one will appreciate your skills and your fund of knowledge, for every medical practice or hospital you apply for, you are a visa holder period!! That is extremely discouraging!”

“Sadly, nephrology is in crisis. Younger generations entering the field do not have the same passion for learning and compassion for patients that I saw in my mentors and that inspired me to go into nephrology. I am simply not as excited about working with the younger generation of colleagues as I am my mentors. I also went into nephrology because of the long-term relationships I could have with my patients. But the way nephrology care is currently practiced (clinic nephrologists, nephronhospitalists, dialysis nephrologists), care is very fractured which only further deteriorates the patient-physician relationship.”

Two fellows who would not recommend nephrology to medical students and residents offered the following input into current discussions of nephrology workforce shortages and fellowship spots:

“ASN needs to understand that even if you get great teachers to teach students or residents, nobody will choose it if they see nephrologists working as hospitalists. (There are many.) Also, renal fellowships are like sweat shops. There needs to be a cap. If one is sleep deprived most of the time, the joy goes away. Absolutely minimal learning. ALSO, IF SPOTS DO NOT FILL, IT SHOULD BE MANDATORY THAT STAFF SHARE THE CALL rather than asking fellows to do so. Spots must be cut down. Period.”

“Despite claims that there is a workforce shortage, a review of the overall numbers suggests that there is currently an excess of nephrologists in the USA (not being able to fill all fellowship spots in a given training program doesn’t connote a national workforce shortage). As such, the efforts of nephrology leadership at this time should not be to add additional warm bodies to the field but rather to officially limit the number of nephrology training spots to only those individuals who are both passionate about nephrology and are sufficiently talented to make nephrology great again. For these reasons, while I am highly satisfied with my choice of nephrology as a career and am very excited to enter the workforce, I would not actively recruit new trainees to nephrology but rather let those who hear the calling seek it out.”